Natural Gas Homes are Lowest-Cost and Lowest-Emissions, Even Compared to Homes with Electric Cold-Climate Heat Pumps

High-efficiency natural gas appliances in homes can lower utility bills and emissions.

A new analysis shows that a typical new home that uses natural gas saves consumers money on energy bills and lowers greenhouse emissions, even compared to high-efficiency all-electric homes. The direct use of natural gas in residential applications can significantly reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions compared with electricity and fuel oil.

The AGA report, Comparison of Home Appliance Energy Use, Operating Costs, and Carbon Dioxide Emissions, evaluates and compares energy costs and emissions for many common home appliances, including natural gas, electricity, propane, and heating oil.

*The study modeled the same typical single-family home that included a furnace, water heater, stove, and dryer operated with different primary energy sources. Oil and propane households use an electric option for dryers, and oil households include an electric stove.

The basis for these findings begins with the cost of the fuel itself. The U.S. Department of Energy has determined that natural gas costs are 3.4 times more affordable than electricity and other residential fuels.

The AGA Appliance Comparison analysis evaluates those energy costs in the context of different appliance configurations, fuel types, and efficiency levels. What does it find?

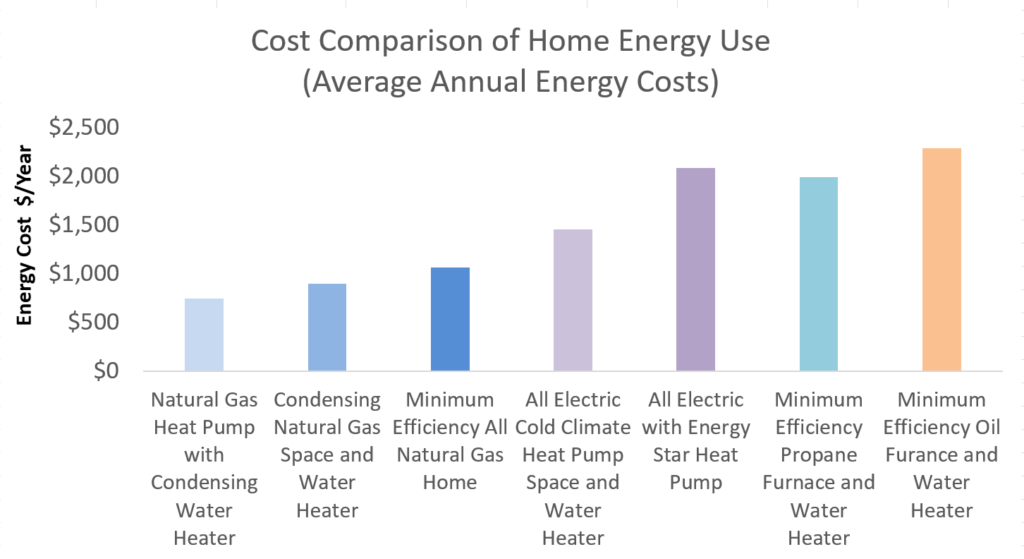

Natural gas homes typically have the lowest energy costs

The higher efficiency and lower price of natural gas relative to other energy forms result in annual utility energy bills for the gas home that are roughly 49 percent lower than the comparable all-electric home energy bills, about 53 percent lower than the oil home, and 46 percent lower than the propane home.

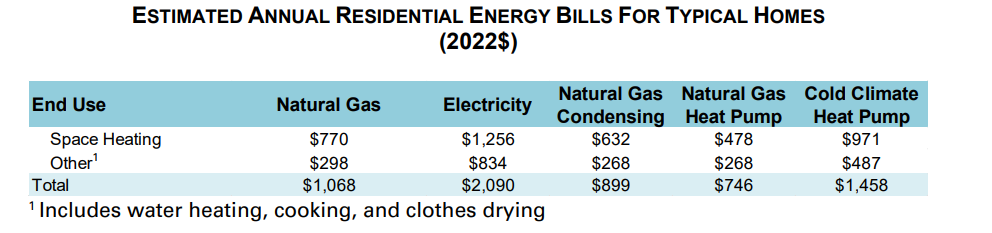

The annual residential energy bill for a typical new single-family home using natural gas for space and water heating, cooking, and drying is $1,068 annually. These appliances are rated at the minimum efficiency requirements specified by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Advanced gas homes save even more. A natural gas home with high-efficiency applications requires less energy and therefore shows a lower average cost of $899. These advanced homes use condensing technology in the furnace or water heater that allows greater capture of more useful energy for space and water heating.

By comparison, an all-electric home with minimum efficiency-rated appliances costs $2,090 annually. The energy cost of the all-electric home using a cold-climate heat pump is $1,458, or 37% higher than the natural gas home. The natural gas home saves an average of $390 per year compared to an electric home with a cold climate heat pump.

The analysis evaluates a “typical new home” energy needs for space heating, water heating, cooking, and drying. The home is assumed to be a one-story, single-family detached residence (2,072 square feet of conditioned space) in an average climate (4,811 heating degree days) constructed to meet the 2013 International Energy Conservation Code. A heating degree day is the number of degrees that a day’s average temperature is below 65 degrees Fahrenheit, which can be added up over a year to evaluate how cold a climate is. Some areas of the country have adopted more recent building codes. In those cases, the assumed energy loads may be lower for the same type of home. Similarly, the temperature-driven loads, such as average space heating requirements, will vary depending on the climate.

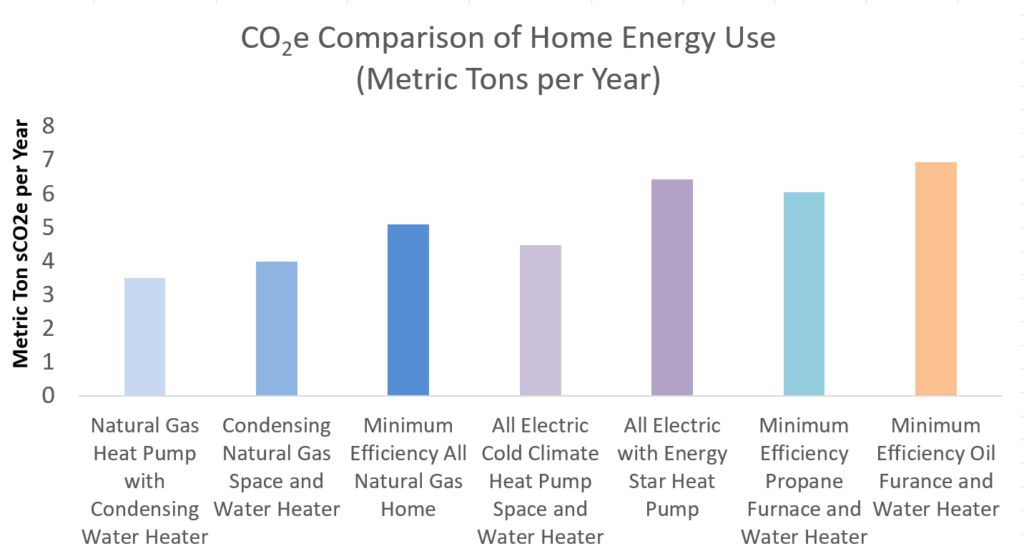

Natural gas homes show lower overall greenhouse gas emissions.

The analysis also examines the greenhouse gas emissions associated with different fuel types and appliances. The use of electricity, natural gas, fuel oil, and propane can lead to carbon dioxide and methane emissions, which can be methodically examined by evaluating the emissions associated with the production and transportation of primary energy to the home emissions at the electric generator. Note that this analysis does not include high-global warming potential refrigerants used in electric heat pumps.

With the installation of high-efficiency condensing natural gas space and water heaters, natural gas homes on average can reach 11 percent lower emissions this year than with the use of many advanced air-source heat pumps, and 21 percent lower emissions than a home with a set of minimum efficiency gas appliances.

In this case natural gas use in residential applications generates significantly less greenhouse gas emissions than electricity, oil, and propane. The emissions resulting from appliance use in a typical newer home are presented here:

Notes: -Emissions from space heating, water heating, cooking, and clothes drying

-Includes impact on CO2 equivalent from unburned CH4

-Emissions estimates are based on the national average generating mix in 2020, which is a conservative assumption. For local analyses, marginal impact methodologies are more accurate than national or regional averages for evaluating the impacts of changes in electricity consumption.

-High-GWP refrigerants used in electric heat pumps not included.

What’s different about this analysis?

These findings may surprise some readers, who have seen other analyses suggesting that electric heat pumps are more affordable than natural gas.

- This analysis uses a full-fuel-cycle approach that includes examining the energy used or lost in energy extraction, processing, transportation, conversion, and distribution, including the generation and transmission of electricity. Full-fuel-cycle metrics account for requirements to bring valuable energy to your home and therefore provide a more comprehensive view of efficiency and emissions associated with consumer appliances.

- Modeled a home that best represents what an existing single-family home built in recent history will look like regarding energy requirements. For most single-family homes with natural gas, the U.S. Census reports that 84% of households have a central heating system. And homes heated with natural gas are, on average, 30% larger.

- Care in evaluating the real-world performance of appliances at different temperature levels. Comparing natural gas appliances with other forms of energy can have many real-world challenges, especially when households are looking for efficiency upgrades that fit their specific home. Ducted heat pumps do work in cold climates, but below-freezing winter temperatures can lead to lower performance, often relying on less efficient backup sources of heating to make up the difference.

- Includes an evaluation of natural gas heat pumps, which can achieve site heating efficiencies greater than 100%. Gas heat pump technology has been around for nearly 100 years (co-invented by Albert Einstein), and modern gas heat pumps are available today in the commercial sector. New residential heat pumps are becoming available right now, supported by industry work and new federal incentives.

In the future, the electric grid be increasingly less carbon-intensive. And so will the gas grid.

The future energy system will not look like it does today. Increasingly, natural gas infrastructure will be used for energy storage and delivering renewable gases derived from biogenic sources and zero-carbon electricity. In addition, next-generation gas technologies like heat pumps, fuel cells, and combined heat and power technologies can take energy efficiency improvements to another level.

AGA is planning additional analysis to examine the energy, costs, and emissions associated with future energy configurations and residential energy options that account for the increased use of renewable energy on the electricity and gas networks and higher-efficiency technologies.

More to come. Stay tuned.